The Next Generation Impact Report: Fighting Poverty 2.0

- Mike Dershowitz

- Dec 10, 2019

- 7 min read

We started collecting data about our Agents and their economic decisions in the last quarter of 2018. We were focused on asking questions like “What do you spend your salary on?” and “What are your proud purchases?” We thought our employees were focused on making their lives better by buying a newer smartphone model or planning a great vacation with a loved one or with friends. These are the things that Americans do whenever they receive their paychecks, right? So, why shouldn’t Filipinos behave the same way? But, that assumption was quickly shot down when we discovered through our impact surveys that most of our Agents’ earnings go into making better the lives of their household members.

Measuring Household Income Against Standard Criteria

Agents’ earnings from a BPO job didn’t just go into their personal spending, but their earnings are distributed among the Agent’s family members. Not just immediate family members, but also cousins, uncles/aunts, grandparents, and even distant relatives. In poorer societies, everyone needs help.

In a typical Filipino household of at least five members, a BPO worker is expected to serve as the primary breadwinner. Some agents are putting a child or several children through school. Others are supporting someone who is sick or disabled. Most of the younger agents are helping their parents pay for utilities and the family’s basic needs. There are even a few whose dependents are unemployed and the Agent is the only one who has the money to buy food for them.

Family is important to Filipinos, and when one has a high-paying job, it’s expected that person will contribute to support everyone in the family. This burden is heavier on the shoulders of the eldest child, whose position grants him or her additional responsibility as the leader and protector of the family.

That’s exactly what the Next Generation Impact Report from Fair Trade Outsourcing wants to study. We’re hoping that studying in-depth into the typical Agent’s household, specifically as seen through the collective spending habits, will help us strategize more effectively our plan in fighting poverty. So, rather than classify economic status by an Agent’s personal income, we followed the PIDS system, which classifies each family of five or more by their household income.

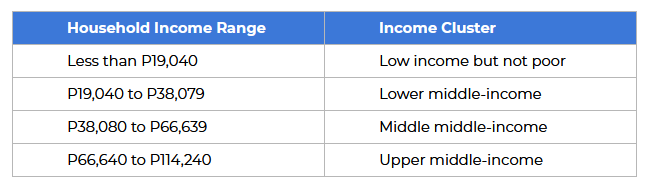

Using the indicative range of monthly family incomes for a family of five at 2017 prices, PIDS groups such families into the following clusters.

While the PIDS study included households living in poverty, the Fair Trade Outsourcing study didn’t. At this point, it’s impossible for FTO to have agents and their families still living below the poverty line, because by always paying a living wage, we know that with our Agents’ current dependency ratio (which is a measure of the number of dependents aged zero to 14 and over the age of 65 compared with the total number of household members), they’re going to be above the poverty line.

The company makes sure that none of its employees receives compensation that’s less than 1.35 times the minimum wage. So, whether the agent is the breadwinner or one of many who contribute to their household, it’s a given that the total household income for any agent will never fall under the low-income-but-not-poor cluster. It’s not enough, but it’s a good start.

Overview of the FTO Survey Results

The PIDS study informed our methodology in gathering data. We promptly revised our impact survey questions to target information we need in order to classify our Agents’ household incomes by the same clusters that the PIDS researchers used.

Based on our collected data, in a month households in the low-income-but-not-poor cluster normally spend beyond what they earn. They’re not earning enough to cover their family’s monthly budget. Most of the money goes to education, food, and allowance for dependents.

Congruent with Banerjee and Duflo’s research, the lower income families tend to spend more on tobacco and alcohol than families in the middle-income clusters. In an article published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives in 2007, Banerjee and Duflo observed that “among the nonfood items that the poor spend significant amounts of money on alcohol and tobacco show up prominently.”

Although the families surveyed by Fair Trade Outsourcing now belong to the low-income-but-not-poor cluster, these families were living in intergenerational poverty before a member of their household became an employee of the company. Habits formed during that time were carried over and continue to be part of the household’s lifestyle.

As the household income increases, the budget becomes manageable despite the huge chunk that food takes out of the family’s monthly earnings. However, the higher the household income, the more the family spends on non-essential expenditures, such as recreational activities. In comparison, upper middle-income households invest some of their earnings into private transportation, which means they were paying off a car loan or spending so much on gas, or both.

The Economic Behavior of FTO Agents and Their Families

In the case of households belonging to the low-income-but-not-poor cluster, their spending habits are dominated by food, education, and their family. Spending on their health and well-being comes second, and they spend nearly as much on recreation and transportation. Apparently, life in the low-income trenches is stressful and can negatively affect one’s health. So, families often dealt with such a povertied existence by giving themselves time to relax and have fun together.

One of the goals of Fair Trade Outsourcing is to raise the quality of life for its employees through middle-class employment. The company already guarantees that none of its employees earns a monthly income that’s below or at minimum wage. In fact, the average gross salary of an employee at Fair Trade Outsourcing is 2.18 times the poverty line.

This monthly income, however, isn’t enough to pull some families out of the low-income clusters. They have many dependents and they’re struggling to survive, especially when they experience financial shocks brought about by a medical emergency, a tragic death in the family, or a catastrophe, such as a fire or typhoon.

We have built a company whose culture emphasizes financial support towards employees. A great example is the COLA that was implemented almost a year ago. Its implementation has helped agents navigate the rising and falling of the country’s inflation rate and the succeeding changes in market prices of basic commodities. When someone joins FTO, the goals is that their economic power in their society never erodes.

In addition, the company has also established a Catastrophe Fund, which provides our employees a sort of lifeline in case a catastrophic event strikes their household and leaves the family in desperate need of money. The working poor rarely have enough free cash flow to save for a rainy day.

All of these efforts, however, are just bandaid solutions. A more effective solution to fighting poverty is to encourage employees to become entrepreneurs themselves. If they can build a thriving small business that will provide their family an additional, sustainable source of income, then their future is set. This is where the Microloans for Small Business program comes in.

In order to become an entrepreneur, an agent who’s been living a life of intergenerational poverty has to overcome a few challenges, such as risk-averse behavior towards investing part of their monthly earnings into a small business that may or may not become successful. Risk aversion is high among the poor, but research has shown that household decision-makers in Asia are more likely to have moderate to intermediate risk aversion compared to households in Africa.

Kihlstrom and Laffont’s theory of entrepreneurship proposes that those who are more risk-tolerant become entrepreneurs. Once we provide assurance that agents who qualified for a small business microloan would be able to pay it back without putting their household income at great risk, they become more enamored at the prospect of becoming entrepreneurs themselves.

As mentioned before, most low-income households tend to spend as much on recreation as they do on their health and well-being. This is a coping strategy that many among the poor practice in order to adapt to the unpredictability of living in poverty, and one that the low-income-but-not-poor families have continued to practice even when they have moved from a life of poverty to a life that’s less mired in financial uncertainty.

The data supports this hypothesis. If you looked at the households in the middle middle-income cluster, you could see that a large portion of their income goes to recreation more than education, health, or even the daily allowance they give to their dependents.

Such behavior can be explained by the concept of bounded reality in economics. It’s the kind of irrational behavior that people with money to spare often display. That’s why stores and malls like to schedule their sales and promotional events on paydays.

Because they experienced scarcity at home when they were in their previous jobs, now that they’re earning more, they tend to gravitate towards splurging on goods or activities that they dreamed about owning or doing with their families. That’s why a television and a cellphone take priority over other durables, such as a refrigerator, that have a potential to reduce their monthly expenses.

Why We’re Calling It a Next Generation Impact Report

The previous impact reports we published since we started our research in 2018 were too focused on individual spending and assumed a lot on the indirect impact of that spending on local businesses. The assumption was that BPO workers earn higher incomes than employees in other sectors. As a result, they have more disposable income, which they spend on business establishments close to their place of work and where they live. But, while consumer spending plays an important role in economic growth, it’s not an effective measurement in the fight against poverty.

Creating more jobs that pay more is just a small part of the struggle to reduce income inequality. The fight against poverty needs a two-pronged approach. Increasing one’s household income is the first step. The second step is to educate people on how to spend their money right and how to grow that income so it’ll benefit not only them but also the people around them.

For this strategy to work, we must have a deeper understanding of how a typical Agent household looks like and how the members behave economically. That’s where the “Next Generation” portion of the Impact Report comes in.

Our impact surveys prove that an Agent will sacrifice the potential for an individual middle-class life afforded by an FTO job in favor of a working poor life where their entire household benefits. This is starkly different from how economists think about poverty, which is that if incomes are high enough, poverty will be reduced.

We also now have a baseline to measure our work against the economic measurements of the societies in which we do business with, effectively proving that a fair trade outsourcing job lifts people out of poverty. Moving forward, we’ll use this new measurement paradigm to boost our impact efforts and direct where our impact spending will go.

Comments